What Did the Nazis Do With the Art They Stole

The masterpieces stolen by the Nazis

(Image credit:

Drove Walker Art Centre, Minneapolis

)

The journeys of looted artworks accept powerful stories that are being explored in a new exhibition, writes Diane Cole.

W

Within the long history of art resides the nearly-every bit-long history of looted art. We are dazzled past these treasures from faraway lands and ancient eras, even as we remain mostly bullheaded to their provenance. Ordinarily left unmentioned is their means of acquisition – all too often, brutally uprooted from their original homes and owners as the spoils of war, colonial conquest, or at the dictate of despots.

More than like this:

- The art hidden from Nazi bombs

- The Nazi art hoard that shocked the earth

- Recovering what the Nazis stole

Until now. Nosotros're reading more than ever about international disputes over buying and restitution, including allegations this week that Switzerland's largest fine art museum might be displaying up to 90 works with problematic provenances. Besides causing controversy recently are stories focusing on the origins – and the fate – of the Republic of benin Bronzes, at least some of which are in the process of finding their way back to Nigeria and Autonomous Republic of Congo from the many countries and museums to which their colonial rulers dispersed them, including Belgium, Germany, the British Museum and New York's Metropolitan Museum.

Such histories of theft and rescue are fabricated more than existent in a powerful new exhibition at New York's Jewish Museum, Afterlives: Recovering the Lost Stories of Looted Art. And they are presented through treasures both artistic and cultural.

Löwenstein'due south 1939 Composition (correct) appears almost paintings by Paul Cézanne (Bather and Rocks, left) and Pablo Picasso (Grouping of Characters, centre) (Credit: Steven Paneccasio)

In the opening galleries, nosotros view one boggling canvas after another by Pierre Bonnard, Marc Chagall, Paul Cézanne, Henri Matisse, Camille Pissarro and other great European modernist painters, each with a story to tell of pillage by the Nazi regime. Many of these works were seized from collectors and artists who happened to exist Jewish; others the Nazis confiscated and slated for oblivion considering they did not conform to Hitler'southward narrow definition of what Aryan art should be – that is, representational and wholesome in their subject matter, as opposed to the frequently abstract, expressionistic compositions that characterised so many modernist works, which they labelled as "degenerate".

And then at that place are the beautiful arrays of delicately crafted ritual silver objects that one time graced the homes and synagogues of the Jews of Europe. They can and should be admired for their craft. But in the context of this evidence, they besides speak even more than powerfully to their crude seizure from their original owners who once wielded them to welcome the Sabbath, gloat the holidays, and observe the milestones of life and expiry, all according to Jewish tradition. Y'all cannot walk through these galleries without thinking of the sense of despoliation experienced past so many people of other cultures throughout history. The emotional pull is visceral.

These objects are the material survivors of the Jewish communities of Europe, each one with a distinct story, an "afterlife" of survival, to reveal. Yet taken as a whole, these tales also adhere to what nosotros might think of every bit a new kind of archetypal journey, one that follows the fate of each piece of work, from the original uprooting of cultural theft to displacement to eventual rescue and restitution.

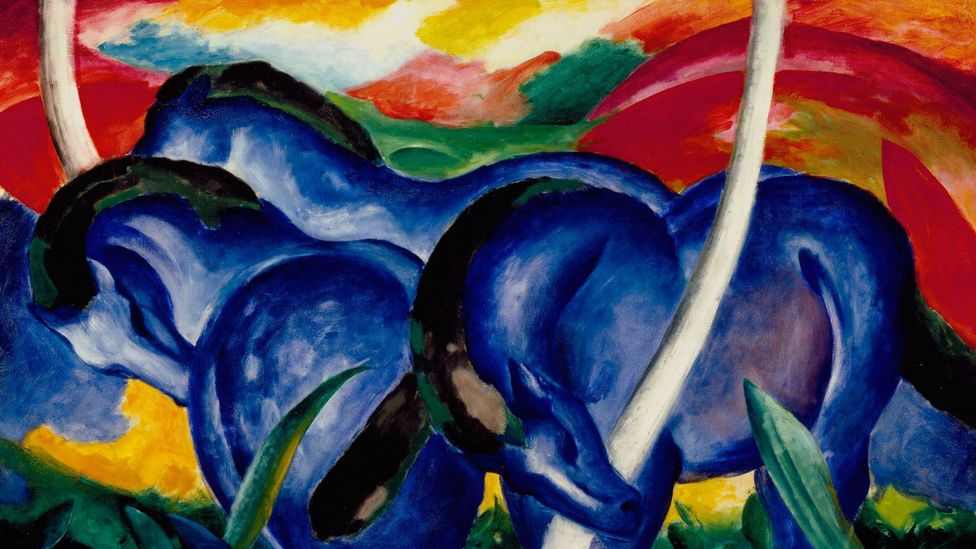

Franz Marc'due south The Large Bluish Horses (1911) was the inspiration for US poet Mary Oliver's 2014 book Blue Horses (Credit: Collection Walker Fine art Heart, Minneapolis)

The divergent roads to such an afterlife are axiomatic from the moment you enter the exhibition. Yous're greeted, first, by the gorgeous sheet by the German Expressionist artist, Franz Marc. The Big Blue Horses, painted in 1911, depicts three vibrantly bluish horses, clustered sensuously together in the foreground, with the hillside behind them done in splashes of blue, ruby-red and green. Although Marc died fighting for Deutschland in World State of war One, Hitler banned his work.

Simply it escaped the Reich'south reach considering in 1938 its German owner sent information technology to London, to be included in an "anti-Hitler" show, and from there it travelled as part of another exhibition, 20th Century Banned High german Art, to the The states, where an American heir-apparent purchased information technology for a collection that is now part of the Walker Art Middle in Minneapolis. It seems thematically fitting that the painting appears hither, on loan once again.

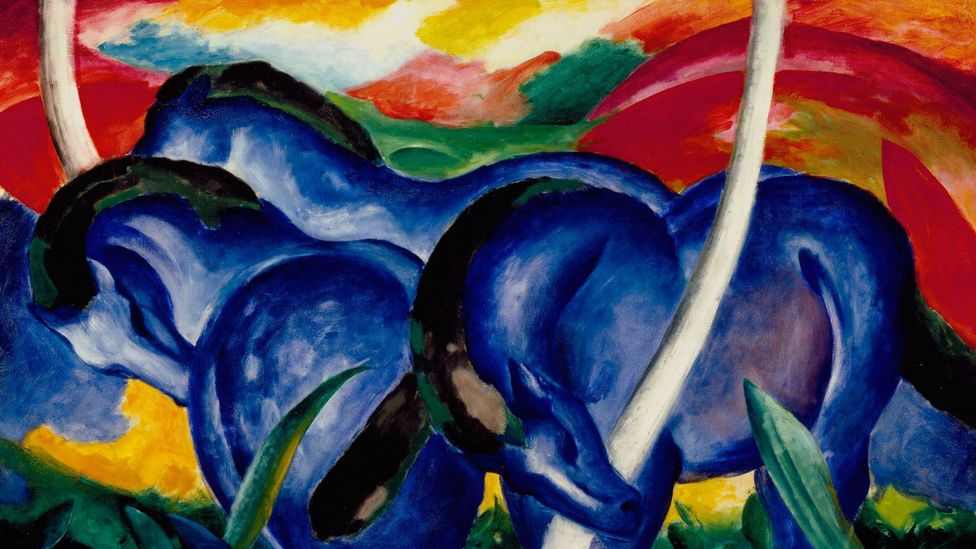

Max Pechstein's 1912 painting, Nudes in a Mural, was restored to the heirs of its Jewish owner in 2021 (Credit: Estate of Hugo Simon)

Near that sheet is a lush, evocative Max Pechstein painting from 1912, Nudes in a Landscape, an exuberant canvas that just this summer was returned past the French authorities to the heirs of the German-born Jewish banker and art collector Hugo Simon. Its murky journey is allegorical of the often long and twisty road travelled by looted art to eventual restitution.

Simon's journeying, as well, was precarious. He fled Berlin for Paris when Hitler came to power in 1933, and after French republic fell to Germany in 1940, he escaped once again, this time to Brazil. Merely the painting was left backside in Paris and seized past the Nazis. It did not plow upward again until 1966, found in storage at the Palais de Tokyo in Paris – yet how it landed in that location remains a mystery. From 1998 on, it was housed at the modern art museum in Nancy, French republic.

Even so Life with Guelder Roses (1892) by Pierre Bonnard, who refused to pigment a portrait of the French collaborationist leader during WW2 (Credit: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art)

Another route to restitution is exemplified in an next sail. The green, yellow, white Impressionist-style 1892 painting by Pierre Bonnard, Still Life with Guelder Roses, was ane of 2,000 pieces stolen by the Nazis from a single collector, David David-Weill, the French-American philanthropist who had headed the cyberbanking house Lazard Frères. This canvass was returned to him in 1946, shortly after it was recovered by Allied forces amidst the many works hidden by the Nazis in an Austrian salt mine.

Hard journeys

The relative smoothness of that recovery makes restitution audio easy, correct? But take a few steps into the adjacent room, and yet another work in the exhibition once over again emphasises the ongoing, perhaps unending work of restitution, in the class of a 1939 Cubist geometric sheet by the German Jewish artist Fédor Löwenstein, that is only at present in the process of being returned to heirs of its original owners by the French government.

Its story also brings habitation the randomness of both survival and restitution. After its seizure, the work had been relegated to a storage infinite at the Jeu de Paume Gallery in Paris that was known as "The Room of the Martyrs". Here, High german officers could select and walk off with stolen masterpieces of their selection; those that remained were often deemed degenerate and slated for destruction. But this one slipped through the cracks and survived, possibly with the help of Rose Valland, the art historian who secretly kept track of the approximately 20,000 works brought there, records that played a cardinal function, mail service-war, in recovering much of the stolen art.

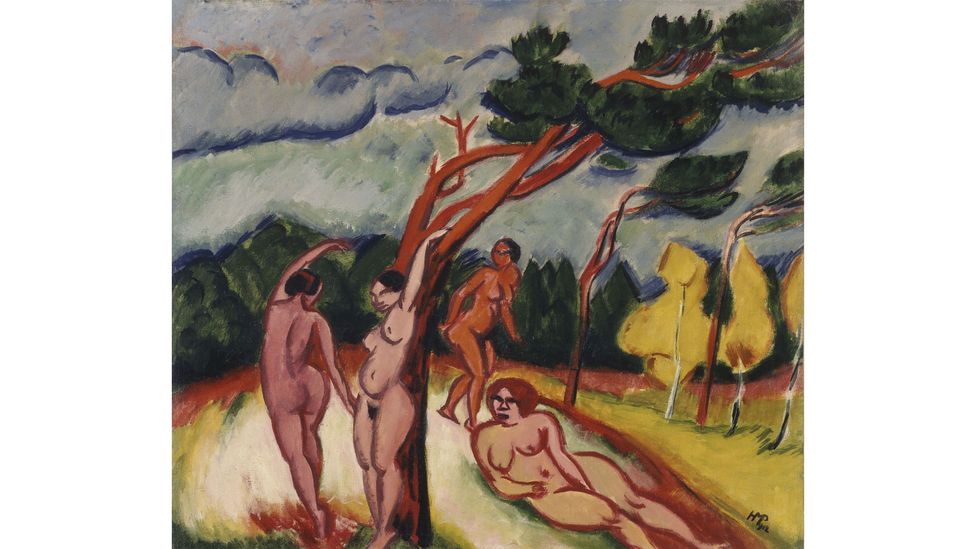

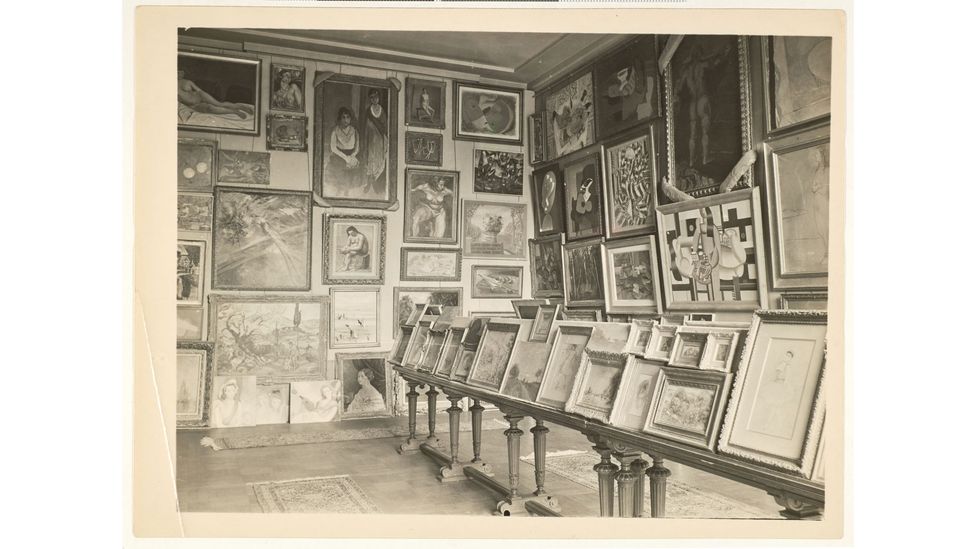

The Room of Martyrs, a storeroom for art banned by the Nazis, at the Jeu de Paume gallery in Paris (Credit: The Jewish Museum)

Yet despite her efforts, Valland could not salve them all, alas. A blackness and white photograph of the room, probably from 1942, shows paintings by André Derain and Claude Monet, amid others, that did non plow upwards postal service-war and most likely were destroyed. It'due south impossible not to plough from this photo with a sense of gratitude for the presence of the glorious works on display here by Paul Cézanne, Pablo Picasso, Henri Matisse, and Marc Chagall, among others.

Nor are viewers allowed to ignore the lives and fates of the families to whom all these cloth possessions at one time belonged. A serial of one-time family photos is lined up on what seems like a living room mantlepiece, intimating what a normal middle-class Jewish family life looked like before the Nazis forced them out. And then, following the Nazi timeline of horror, comes a collection of portraits and drawings made in secret, then hidden, by artists interred in Nazi concentration camps.

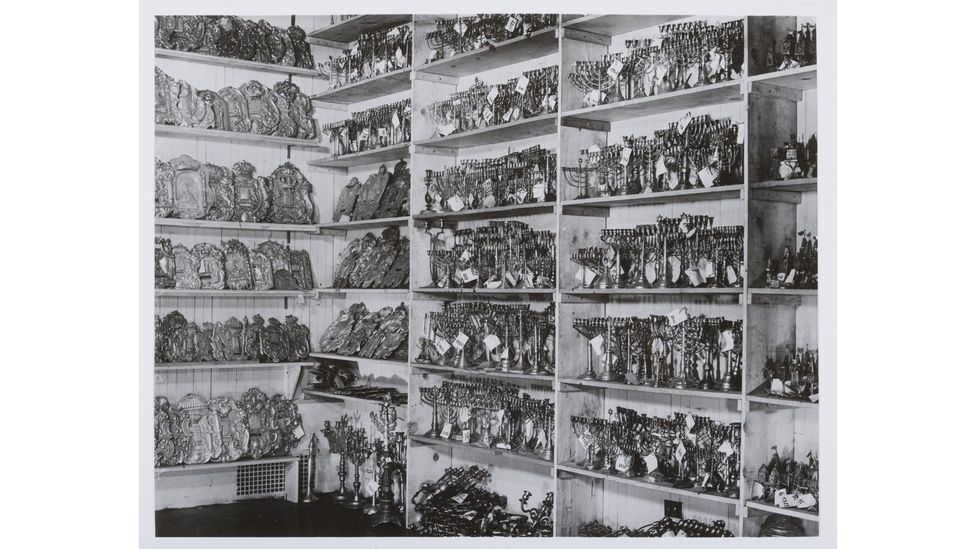

Ritual objects were rescued by Jewish communities as part of a wider salvage endeavor (Credit: The Jewish Museum)

Perhaps it's no wonder that walking through the galleries, I often felt immersed in a world turned topsy-turvy by theft, never more and so than as I gazed at the vitrines of Jewish ritual objects – Kiddush cups, Sabbath candle sticks, Torah pointers, and other holy objects – lined up aslope each other as if for a massive warehouse auction, with no community, perhaps no person, alive to claim them. That is, until the surviving Jewish communities outside of Europe – including the Jewish Museum in New York – stepped in after the war to help rescue the many orphaned objects. All the ceremonial works on display in this exhibition establish their own afterlives as part of the Museum'due south permanent collection, a part of that massive endeavour to salvage the remains of European Jewish culture.

Looking forward

That the legacy of stolen fine art and cultural objects likewise leaves ghostly afterlives in subsequent generations is the subject field of the final department of the exhibition: new works commissioned by four young gimmicky artists living in State of israel, Berlin, and Brooklyn: Maria Eichhorn, Hadar Gad, Dor Guez, and Lisa Oppenheim.

Each of these artists approaches this history from a dissimilar perspective. Conceptual artist Eichhorn immerses us in the very work of recovering, locating, and returning looted objects. She does so by surrounding us with actual cases of archival papers, ledgers, reports, books, and on and on, all needed to verify, certify, analyse, authenticate each antiquity, each item. Further intensifying the sense of being thrust into the work itself is the sound backdrop of an ongoing, non-stop recording of the phonation of philosopher Hannah Arendt. She is reading various memos she wrote in her chapters as a director of the bureau tasked with the deplorable simply urgent goal of sorting through the massive crates of materials that were recovered.

Dor Guez'south installation is based on a manuscript from his family'due south archive that belonged to his paternal grandpa, a Holocaust survivor (Credit: Steven Paneccasio)

In his installation, Dor Guez, the son of a Palestinian mother and a North African Jewish father, creates a museum-style display of objects, documents and prints to bring to life again the multiplicity of losses of his family's Judeo, Tunisian, and Arabic languages and culture. Hadar Gad's powerful big-calibration, dream-similar collage paintings are based on historical photographs of the backwash of the destruction of Jewish property by Nazi soldiers. Finally, Lisa Oppenheim bases her series of mysteriously overcast photo-collages on the only remaining image of a nonetheless-life painting – by the Franco-Flemish painter Jean-Baptiste Monnoyer – that disappeared later its confiscation past the Nazis from a Jewish household in Paris.

These, and so, are the afterlives that remain. The emotional impact of the exhibition is overwhelming: joy and gratitude at the rescue of and then many exquisite artworks; grief at the losses endured by the destroyed Jewish communities of Europe; and finally comfort in the cognition that their stories practice endure. In that location might even be a blink of hope that these narratives could also bring some perspective in resolving the many ongoing restitution cases effectually the world. In the meantime, the archetypal journeys of the world's looted artworks continue.

Afterlives: Recovering the Lost Stories of Looted Fine art is at New York's Jewish Museum until 9 January, 2022.

If you would similar to comment on this story or annihilation else yous have seen on BBC Culture, head over to our Facebook folio or message us on Twitter .

And if you liked this story, sign upward for the weekly bbc.com features newsletter , called The Essential Listing. A handpicked pick of stories from BBC Hereafter, Culture, Worklife and Travel, delivered to your inbox every Fri.

Source: https://www.bbc.com/culture/article/20211123-the-masterpieces-stolen-by-the-nazis

0 Response to "What Did the Nazis Do With the Art They Stole"

Post a Comment